Brent Bradbury is the VP of Software at Boltline, a company spun out of Stoke Space after years of building internal software to support a fully reusable launch vehicle.

The following conversation covers how Stoke approached software across design, manufacturing, and test; what iteration actually looks like inside a launch vehicle program; and which lessons apply more broadly to teams building complex hardware at speed.

"Stoke didn’t set out to build software. We set out to build hardware, and the tools got in our way. While we were still in early prototyping, it became clear we needed a unified system to manage engineering and production, one that offered traceability, repeatability, and audit readiness."

Origins from Stoke Space

Can you take us back to the early days of Stoke Space? What were you building, and what problem were you setting out to solve?

From the start, we were focused on building a rocket that is fully and rapidly reusable. SpaceX of course proved the first stage could be reused, which fundamentally changed launch economics. But most of the cost and complexity in a launch system lives in the upper stage. If the second stage is still expendable, you never get to an airline-like operational cadence. So our premise was simple: both stages need to fly, return, and fly again with minimal maintenance.

That drove a lot of the architecture choices, especially the actively cooled heat shield and uniquely designed second stage. What we really understood very early is that our real constraint isn’t just the hardware, it’s how quickly we can iterate. To get a system like this right, you need to design, build, test, and repeat with clear traceability of what changed between each iteration. That is where software naturally became central.

Across a launch vehicle organization, software touches a lot of subsystems like propulsion, avionics, simulation, operations. How do you think about building for such different domains?

We run a unified software organization that builds reusable software rather than separate teams building one-off systems for each domain. For example, the same runtime that controls the rocket also controls our test stands. That means control logic, verification, and fault handling are developed once and exercised continuously throughout development.

On the data side, we keep a single data tier that combines time series data from tests and flights with the BOMs and configuration histories that come out of manufacturing. Everyone is operating against the same understanding of what was built, what was tested, and what flew. From there, we only add thin layers for the needs of specific teams..

Building Boltline

Walk us through a real development cycle for a launch vehicle program. Where does software play the biggest role?

The cycle is design, build, test, analyze, and repeat.

We often rebuild hardware and retest it in under a day. Each test introduces many changing variables, and engineers have to keep track of the performance of their system even considering that. They must be able to create a snapshot of the configuration of the hardware for each test.

Software is where we preserve the state and intent of the hardware across that cycle. It makes sure the test you run is actually testing what you think it is, and that the data you gather is grounded in the real configuration that was on the stand.

What does using Boltline look like day-to-day for an engineer or technician?

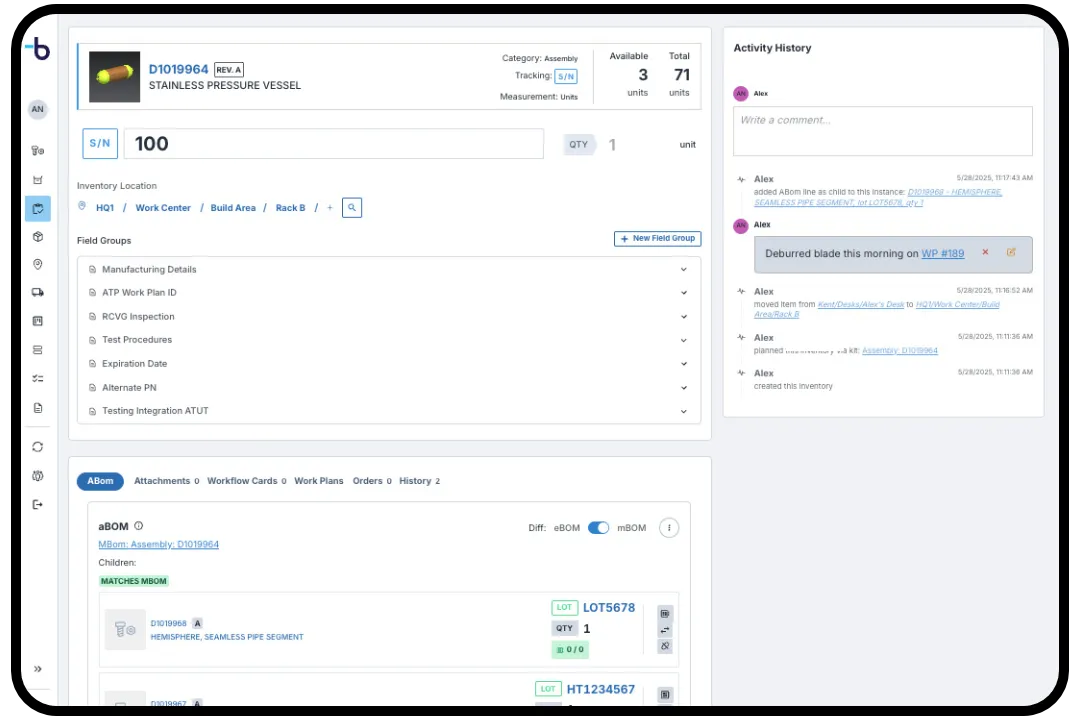

For an engineer, Boltline is where design intent turns into something that can actually be built. You see your open work, the change history, what has been tested, what passed, what failed, and what is being fabricated right now.

For a technician or operator on the floor, Boltline is the authoritative build guide. Procedures, torque values, sign-offs, configuration steps, and the exact revision of the hardware you are working on. And it updates in real time as things change.

It covers parts of MES, but it extends upstream into engineering and downstream into test and operations. The goal isn’t to fit an industry category. The goal is to make continuous hardware development workable at high speed.

Broader Landscape

What does good communication between hardware and software teams look like?

That’s a very different answer depending on what the software team is supporting. For avionics, it looks like putting firmware authors and hardware engineers in neighboring desks. For control systems teams, that means creating a shared understanding of the hardware that is being controlled and giving the right tools to the operators. For Boltline it means organizing all of the end-to-end connections people want to make with the tool, then making the details lovable.

Do the lessons from rockets carry into other domains?

Yes. Any organization building hardware at high speed with meaningful consequences for mistakes runs into the same problems. Aerospace, defense, robotics, energy systems, EV hardware. The patterns are the same: high iteration, high traceability, and high need for clarity

Where do you want Boltline to be in five years?

I want Boltline to be the system of record for every high-cadence hardware organization. Not a supplementary tool, but the backbone that design, manufacturing, test, and operations all connect to.