Electronics manufacturing is one of the world’s largest industrial footprints, threaded through a massive share of modern supply chains. Every modern device — medical sensors, aircraft avionics, industrial controls, even the cheap consumer gadgets we throw away — runs through the same global machinery of PCB fabrication, assembly, test, and verification. It’s a huge industry, but most of it is invisible because the work happens in distributed, specialized factories that sit behind brand names and glossy enclosures.

We recently had the chance to tour Express Manufacturing, Inc. (EMI), an electronics manufacturer based in Southern California. Touring a shop like EMI is a reminder that electronics aren’t “made” so much as they’re assembled, qualified, and proven across dozens of tightly controlled steps. Once you see that system up close, it’s easier to understand why building reliable electronics at scale is hard, and why the shops that do it well are worth studying.

What follows is a factory-floor walkthrough, equal parts education and the day-to-day mechanics of electronics production.

About Express Manufacturing, Inc. (or just EMI)

EMI is one of the largest electronics manufacturing services (EMS) shops in Southern California, founded in 1982 and grown over four decades into a six-building network across the region. It’s still family-owned, and the scale shows: this facility runs everything from PCB assembly to full product assembly, along with installation, test, and whatever QA a customer’s program requires. Despite operating only two shifts with a little over 100 employees, they shipped close to a million units in a single month last calendar year — a reminder of how much volume a well-run, high-mix EMS operation can push through a single site.

Where It Starts: An Idea, Consignment, or Turnkey

The flow to work with EMI is simple for those familiar with buying manufacturing services. Companies can choose consignment or turnkey for fabrication, and also make use of engineering value-add services to boost the bandwidth of internal engineering departments.

With turnkey manufacturing, companies allow the shop to excel at what they do best; that is, sourcing parts, managing vendors, and running builds end-to-end. With consignment, customers supply some or all of the materials, and the manufacturer charges for labor, processing, and assembly. In this model, you retain ownership of the supply chain and take on more of the integration risk.

Most often a supplier like EMI can do a better job of buying components, getting boards made, and designing test fixtures than you can. For example, they have a longstanding relationship with Summit Interconnect for board fabrication (see our tour of Summit’s Hollister facility here).

That said, there are cases where consignment is required or the best option available. If customers are using controlled components a manufacturer can’t source, you have to consign them. If a program requires a company to stick with certain subcontracted suppliers—because of internal agreements, regulatory constraints, or customer requirements—consignment is the only path. And while it’s less common, sometimes companies genuinely have a cost advantage and can procure certain parts or services cheaper than the CM.

Reels of components stacked and ready to go

Then there’s the case where companies don’t actually have much engineering work done yet and instead bring a concept for the product. In that situation, it’s usually best to lean on as much turnkey support as possible. Let the contract manufacturer do what they’re optimized for, and free up internal engineering bandwidth available for parts of the design that truly need it.

No matter which path you choose, all paths point to the shop floor in the end. Specifically, the design for manufacturing (DFM) and new product introduction (NPI) departments. These teams make sure the design is ready for production and chart how the product will flow into the equipment and processes the factory actually runs.

Pink trays ready for selective soldering at EMI.

Types of Soldering Machines

For most jobs, manufacturing at EMI starts with soldering. PCBs and mechanical enclosures are fabricated off-site by other vendors, so before the PCBA can be mounted into the enclosure, it first must be assembled. That means populating the bare PCB with components and soldering them in place. In practice, it’s exactly what you’d expect: parts are picked, placed, and reflowed onto the board to turn a piece of fiberglass into a functioning electrical system that can then be integrated into the product.

Reflow Oven

Reflow ovens are the most common type of soldering method in high-volume assembly and how most components are assembled to boards. Solder paste is applied to the PCB via a stencil, and then the PCB components are robotically placed onto the board. At each stage, there are inspections: the paste is inspected once it is applied, components are inspected once they are placed, and the end PCBA once it is soldered.

Photo: Multi-stage reflow oven line processing PCBs.

There are a lot of finer points to running reflow ovens like:

- The component. Components have to be fed in by reels, and there’s a limit on how many reels (and thus unique components) a machine can be fed. EMI has a great system of loading the components onto a cart, and then if a project needs more than one cart, they have it loaded and ready to be used.

- Component attrition during placement. Electronic components cannot be removed from the reel and placed on the board with 100% yield; some fall off, and are often too small and fragile to be recovered. The manufacturer has to slightly overestimate the component count by ~5% (depending on the component) to have enough for the order.

- Understanding the optimal thermal profile. Especially for applications like aerospace and defense, where a combination of high temperature and vibrations can be expected, engineers will specify the right type of solder that can activate to be strong enough for the job. The solder has to be stored at the right temperature, and most importantly, the oven has to ramp up to temperature at a certain rate and also cool at a certain rate to ensure effective wetting of the solder.

- Wetting is the term used to describe how solder fuses into the crystal lattice of both the component lead and PCB.

Automated assembly covers the bulk of the board assembly. Double-sided designs require a second pass after flipping, and a small set of parts — typically large, heavy, or heat-sensitive — are installed manually downstream.

Wave Soldering

Wave soldering is how thru-hole components are installed. Once the industry standard, this method of soldering became less popular once surface-mount components were introduced as the industry miniaturized.

With wave soldering, ingots of solder are melted into a bath of molten material. The level of the solder is critical; surface tension is used to keep the liquid solder in contact with the PCB as it moves over the top of the solder path. This allows the solder to completely wet the component lead and wick into the barrel of the thru-hole, without flowing onto the surface of the PCB above.

Wave soldering machine with molten solder bath.

Selective Soldering

Selective soldering is used when a mix of thru-hole and surface-mount technology is in use. However, selective soldering is only used to install the remaining thru-holes after the PCB goes through the pick-and-place process and reflow oven.

In selective soldering, a smaller bath of solder is maintained and then robotically actuated in a path that solders all of the thru-holes while avoiding the surface mounts.

Trays ready for selective soldering operations.

Hand Soldering

Hand soldering is used in applications where no other method of assembly is suitable. Often it’s just a handful of components that need manual care, like heavy components on a two-sided PCB that might fall off, sensitive components that cannot handle the thermal profile of the solder oven, or custom components that require extra additional inspection. EMI has what is by far the largest hand soldering capacity we’ve seen from a manufacturer, so there is probably no hand soldering job which is too big for them to handle.

Photo: Dedicated hand soldering bays with magnification tools.

De-Panelization

During the entire assembly process, the pick-and-place machines and reflow oven operate on a larger panel of boards, with boards densely packed for material optimization. The panel is designed to use material as efficiently as possible, and following the assembly process, all of the PCBAs are cut out of the panel.

An Automated de-panelization router in action.

De-panelization is the most common manufacturability issue EMI sees. If designs don't leave optimal locations for the supports to be cut into the board, then the PCBs may have to be de-panelized ahead of time.

Manufacturers like EMI can accommodate this by designing custom fixtures to hold the boards in place during assembly, but understandably, there’s a lot of efficiency to be gained by offsetting any components that are in a critical position for de-panelization.

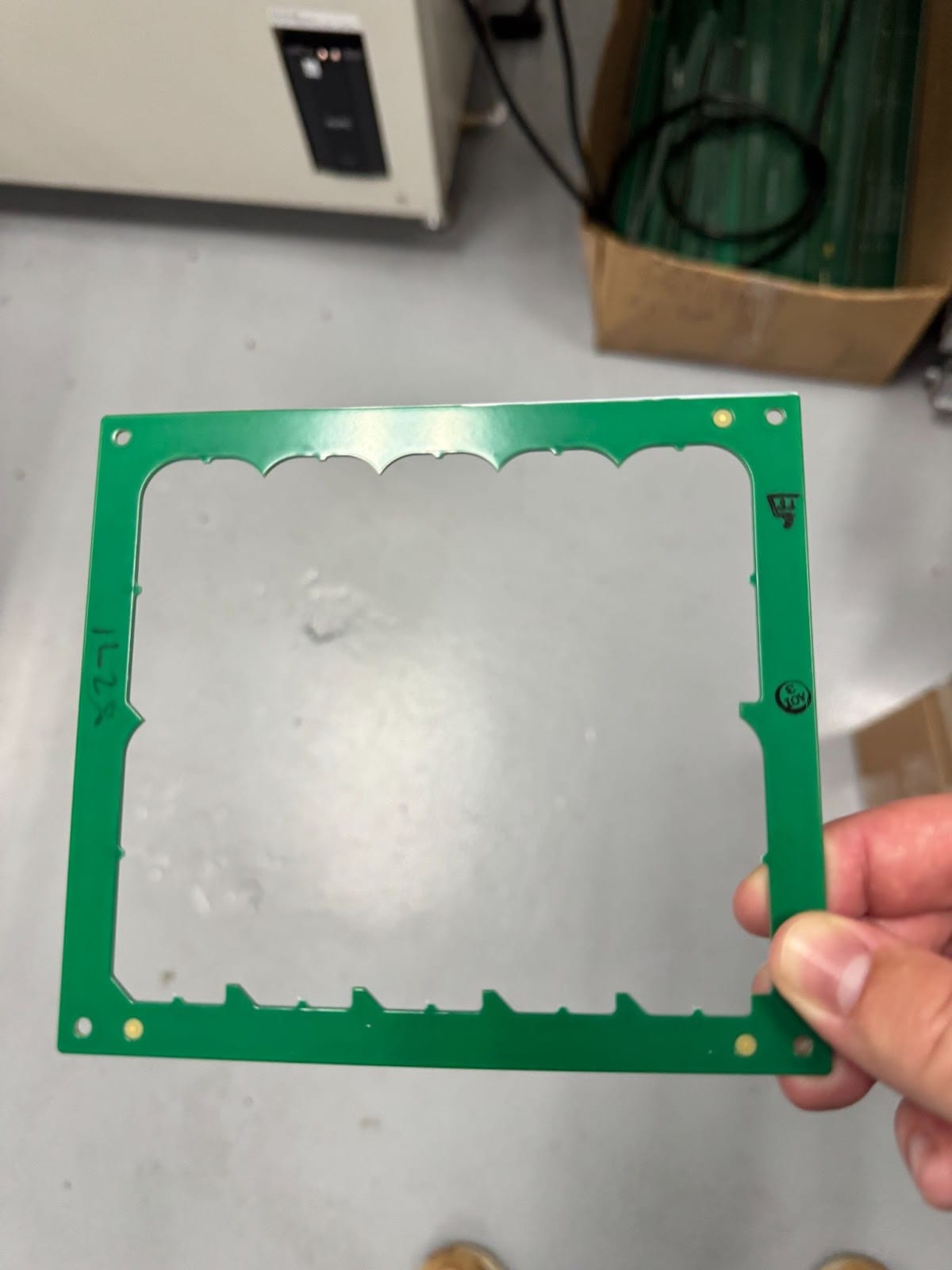

An example of a custom fixture that holds PCB panels during assembly.

Custom fixture holding PCB panels during assembly at EMI.

Inspections and QA

Once boards come off the soldering line, the work is far from done. Every assembly step is paired with inspection (some automated, some human, and often both) before a product is allowed to move downstream. At EMI’s facility, entire machines are dedicated to inspection alongside factory operators who perform their own quality checks on both the equipment and the product moving through the line.

AOI: Machine-Run Inspections

One of the biggest differences between a professional EMS and a small shop is the inspection equipment available on hand. Automated optical inspection (AOI) machines perform high-resolution scans of assembled PCBAs, comparing each board against a known-good “golden” reference. AOI can flag issues like missing components, placement errors, polarity mistakes, and solder bridging that are easy to miss by eye.

AOI doesn’t replace human inspection, but it excels at consistency; every board is checked against the same baseline before the product moves forward.

Modern AOI’s can provide operators with advanced 3D visualizations to help chase down the problem.

Flying Probe Test

To validate electrical integrity, EMI uses flying probe testing to check continuity, shorts, and resistance at exposed test points. Movable probes traverse the board without a custom fixture, making this approach well-suited for prototypes and high-mix, low-volume programs.

At EMI, flying probe tests run post-reflow, catching opens, shorts, and resistance issues before boards reach downstream assembly, where failures become more expensive to fix.

Inspection Stations

EMI also operates manual inspection stations where technicians check form, fit, and function using microscopes and bench-top test equipment. These can be simple power-ups to verify basic operation, visual checks to areas flagged by automated test equipment, and randomized quality checks that EMI mandates as part of their zero-defect philosophy. At these stations, technicians can probe solder joints for voids or measure tolerances down to microns.

What stood out during the tour was the integration from AOI to manual inspection stations. Boards flagged by AOI or electrical test route directly to these stations, creating a tight feedback loop that resolves issues without stalling the line.

For many programs, visual and electrical inspection is one of several gates. Products that need to survive real operating environments then move on to environmental qualification.

Environmental Chambers

Environmental chambers verify that the product can meet temperature and humidity specifications. EMI has thermal chambers, some of which have humidity control and can verify that a device functions properly both during operation and outside of operation. These chambers simulate extreme conditions to stress-test electronics for durability and performance. For instance, the chambers can cycle temperatures from -40°C to +150°C while monitoring humidity levels up to 95%, ensuring components and the board itself won't warp, crack, or degrade under real-world stresses.

High temperature testing is especially important for products operating in confined or thermally harsh environments, like automotive dashboards or sealed industrial enclosures, where electronics must survive elevated ambient temperatures. For programs that require it, some of their chambers can combine temperature, humidity, and vibration testing into a single unit, to mimic the effects of mechanical loads.

Conformal Coating

Once environmental and electrical testing are complete, boards that require additional environmental robustness move to conformal coating.

Conformal coating is applied after the PCBA has been fully assembled, soldered, cleaned, inspected, and electrically tested. This timing ensures that any defects are identified and corrected before they are permanently sealed beneath the protective layer, while still allowing the coating to be added once the board is confirmed functional and ready for long-term service. In standard flows, the coating step occurs near the end of the electronics manufacturing sequence; typically immediately after final functional testing.

The process involves masking connectors, switches, test points, and other keep-out areas, followed by automated selective spraying, brushing, or dipping to deposit a uniform layer of acrylic, urethane, silicone, or parylene across the area. After controlled curing (UV, thermal, or moisture), a final thickness and visual verification is performed, and the coated assembly is released to the next operation.

Conformal coating machines in use

Product-Specific Testing

Then we get into the fun stuff, with product-specific testing. At this stage, the customer defines the functional requirements, and a test fixture is designed around the product’s interfaces. These fixtures are custom to each program and interface with automated scripts to perform functional verification, boundary scans, firmware programming, and, where required, regulatory checks like FCC emissions.

During the tour, we saw the testing process for a breathalyzer that used different dilutions of ethanol gas to test whether the device can detect the required thresholds of alcohol in someone’s breath, with the fixture automating gas flow and sensor calibration for repeatable results. We also saw in-flight entertainment systems (the screens on the back of airplane seats) set up and tested for burn-in—running 24/7 test images to weed out early failures. And there were numerous product test fixtures used for programming firmware, stress-testing under load, and other functions, all designed collaboratively with the client.

Deep Dive on the Finer Points

How Pick-and-Place Machines Are Loaded

Pick-and-place machines are loaded using carts of components staged ahead of the line. These machines place on the order of 100,000 components per hour and draw from feeder carts stocked with tape-and-reel parts, trays, or tubes. At EMI, carts are wheeled to the machine stations and docked, where vacuum nozzles or grippers align and pick components. Jobs begin with barcode scans for traceability, followed by automatic calibration to account for component size variation, from 01005 passives to larger QFNs. For higher-mix builds, carts can be swapped without fully tearing down the line, limiting downtime between jobs.

X-Ray Counting and Reel Attrition

An X-ray system is used to count components on full reels prior to loading. The system images the reel to determine which tape positions are populated, producing a non-destructive count without opening moisture-barrier packaging. Counts account for typical reel attrition—empty pockets or placement losses—which can range from 2–5% depending on component type. These counts are used to reconcile kitting quantities before builds begin.

Line Configuration Across Facilities

Production lines are configured identically across facilities. A process developed on the Santa Ana lines can be transferred to lines in Vietnam or China without changing feeder types, software, or core setup parameters. This allows builds to move between sites without requalifying the process.

How Pick-and-Place Machines Are Loaded

Pick-and-place machines are loaded using a cart of components, but there's more to it than meets the eye. These high-speed robots are capable of placing up to 100,000 components per hour, and rely on feeder carts stocked with tape-and-reel parts, trays, or tubes. At EMI, operators wheel in pre-loaded carts to the machine's stations, where vacuum nozzles or grippers align and pick parts. The process starts with barcode scanning for traceability, followed by auto-calibration to handle varying component sizes—from tiny 01005 passives to larger QFNs. For complex jobs, EMI's setup allows quick swaps between carts, minimizing downtime and supporting just-in-time inventory flows. This efficiency is key in turnkey ops, where accurate loading directly impacts cycle times and yield.

X-Ray Machine for Component Counting, Attrition Rate on Reels

EMI also has an X-ray machine just for loading components. It X-rays the full reel and determines which locations on the tape have components, providing an instant, non-destructive count that beats manual verification by orders of magnitude. Using AI-enhanced imaging, it scans through moisture-barrier bags to tally parts with 99.9% accuracy, accounting for the 2-5% attrition from pick-and-place drops or empty pockets. This isn't just about numbers—it's supply chain insurance, preventing production halts from undercounted reels and enabling precise kitting for consignment jobs. In our tour, seeing it in action highlighted how such tech integrates with EMI's ERP system for real-time inventory syncing.

How Lines Are Configured Across Facilities

All of EMI’s lines are identically configured across their facilities. That means you can take a process you developed on the lines in Santa Ana and run it directly on some of the overseas lines at their Vietnam and China facilities. This standardization, down to feeder types and software protocols, reduces transfer times from weeks to days, supporting hybrid onshore-offshore models that balance cost and IP security. For global clients, it's a game-changer: prototype in the U.S. for speed, scale in Asia for volume, all while maintaining consistent quality metrics like 99.5% on-time delivery.

Employee Training

EMI does all their own training in-house! The size of the operation means that they train their own IPC instructors in-house and can bring a prospective technician up to speed with the right processes in just a few months. Aligned with IPC standards, these programs blend classroom theory with hands-on labs, certifying techs in everything from ESD handling to advanced rework. What sets EMI apart is the customization: modules tailored to client specs, like aerospace vibration soldering, ensuring a workforce that's not just certified but production-ready from the start.

Touring a factory is a reminder that manufacturing, like all engineering, is a discipline of details. The best shops manage the choreography end-to-end, pulling a high-mix design into production while keeping tight control over process, quality, and yield.

Huge thanks to EMI—and especially Jason and Emily—for opening up the facility and letting us walk the floor!